- Home

- Ian Mcewan

Nutshell

Nutshell Read online

Also by Ian McEwan

First Love, Last Rites

In Between the Sheets

The Cement Garden

The Comfort of Strangers

The Child in Time

The Innocent

Black Dogs

The Daydreamer

Enduring Love

Amsterdam

Atonement

Saturday

On Chesil Beach

Solar

Sweet Tooth

The Children Act

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2016 by Ian McEwan

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape, an imprint of Vintage Publishing, a division of Penguin Random House Ltd., London, in 2016.

www.nanatalese.com

DOUBLEDAY is a registered trademark of Penguin Random House LLC. Nan A. Talese and the colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Ian McEwan is an unlimited company, no. 7473219, registered in England and Wales.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

Curtis Brown, Ltd., and Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC: excerpt of “Autumn Song” from W. H. Auden Collected Poems by W. H. Auden, copyright 1937 and renewed 1965 by W. H. Auden. Reprinted by permission of Curtis Brown, Ltd., and Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

John Murray, an imprint of Hodder and Stoughton Ltd.: excerpt of “Indoor Games Near Newbury” from Collected Poems by John Betjeman, copyright 1955, 1958, 1962, 1964, 1968, 1970, 1979, 1981, 1982, 2001. Reprinted by permission of John Murray, an imprint of Hodder and Stoughton Ltd.

Cover design by Suzanne Dean

Cover illustration: Detail from Five Views of a Foetus in the Womb by Leonardo da Vinci © Bibliotheque des Arts Decoratifs / Archives Charmet / Bridgeman Images

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: McEwan, Ian, author.

Title: Nutshell : a novel / Ian McEwan.

Description: First American edition. | New York : Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, [2016]

Identifiers: LCCN 2016026696 (print) | LCCN 2016033596 (ebook) | ISBN 9780385542074 (hardcover : acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780385542081 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Pregnant women—Fiction. | Married women—Fiction. | Marital conflict—Fiction. | Adultery—Fiction. | Psychological fiction. | BISAC: FICTION / Literary. | FICTION / Family Life. | FICTION / Psychological. | GSAFD: Suspense fiction.

Classification: LCC PR6063.C4 N84 2016 (print) | LCC PR6063.C4 (ebook) | DDC 823/.914—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016026696

ebook ISBN 9780385542081

v4.1

ep

Contents

Cover

Also by Ian McEwan

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

A Note About the Author

To Rosie and Sophie

Oh God, I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space—were it not that I have bad dreams.

SHAKESPEARE, Hamlet

ONE

So here I am, upside down in a woman. Arms patiently crossed, waiting, waiting and wondering who I’m in, what I’m in for. My eyes close nostalgically when I remember how I once drifted in my translucent body bag, floated dreamily in the bubble of my thoughts through my private ocean in slow-motion somersaults, colliding gently against the transparent bounds of my confinement, the confiding membrane that vibrated with, even as it muffled, the voices of conspirators in a vile enterprise. That was in my careless youth. Now, fully inverted, not an inch of space to myself, knees crammed against belly, my thoughts as well as my head are fully engaged. I’ve no choice, my ear is pressed all day and night against the bloody walls. I listen, make mental notes, and I’m troubled. I’m hearing pillow talk of deadly intent and I’m terrified by what awaits me, by what might draw me in.

I’m immersed in abstractions, and only the proliferating relations between them create the illusion of a known world. When I hear “blue,” which I’ve never seen, I imagine some kind of mental event that’s fairly close to “green”—which I’ve never seen. I count myself an innocent, unburdened by allegiances and obligations, a free spirit, despite my meagre living room. No one to contradict or reprimand me, no name or previous address, no religion, no debts, no enemies. My appointment diary, if it existed, notes only my forthcoming birthday. I am, or I was, despite what the geneticists are now saying, a blank slate. But a slippery, porous slate no schoolroom or cottage roof could find use for, a slate that writes upon itself as it grows by the day and becomes less blank. I count myself an innocent, but it seems I’m party to a plot. My mother, bless her unceasing, loudly squelching heart, seems to be involved.

Seems, Mother? No, it is. You are. You are involved. I’ve known from my beginning. Let me summon it, that moment of creation that arrived with my first concept. Long ago, many weeks ago, my neural groove closed upon itself to become my spine and my many million young neurons, busy as silkworms, spun and wove from their trailing axons the gorgeous golden fabric of my first idea, a notion so simple it partly eludes me now. Was it me? Too self-loving. Was it now? Overly dramatic. Then something antecedent to both, containing both, a single word mediated by a mental sigh or swoon of acceptance, of pure being, something like—this? Too precious. So, getting closer, my idea was To be. Or if not that, its grammatical variant, is. This was my aboriginal notion and here’s the crux—is. Just that. In the spirit of Es muss sein. The beginning of conscious life was the end of illusion, the illusion of non-being, and the eruption of the real. The triumph of realism over magic, of is over seems. My mother is involved in a plot, and therefore I am too, even if my role might be to foil it. Or if I, reluctant fool, come to term too late, then to avenge it.

But I don’t whine in the face of good fortune. I knew from the start, when I unwrapped from its cloth of gold my gift of consciousness, that I could have arrived in a worse place in a far worse time. The generalities are already clear, against which my domestic troubles are, or should be, negligible. There’s much to celebrate. I’ll inherit a condition of modernity (hygiene, holidays, anaesthetics, reading lamps, oranges in winter) and inhabit a privileged corner of the planet—well-fed, plague-free western Europe. Ancient Europa, sclerotic, relatively kind, tormented by its ghosts, vulnerable to bullies, unsure of herself, destination of choice for unfortunate millions. My immediate neighbourhood will not be palmy Norway—my first choice on account of its gigantic sovereign fund and generous social provision; nor my second, Italy, on grounds of regional cuisine and sun-blessed decay; and not even my third, France, for its Pinot Noir and jaunty self-regard. Instead I’ll inherit a

less than united kingdom ruled by an esteemed elderly queen, where a businessman-prince, famed for his good works, his elixirs (cauliflower essence to purify the blood) and unconstitutional meddling, waits restively for his crown. This will be my home, and it will do. I might have emerged in North Korea, where succession is also uncontested but freedom and food are wanting.

How is it that I, not even young, not even born yesterday, could know so much, or know enough to be wrong about so much? I have my sources, I listen. My mother, Trudy, when she isn’t with her friend Claude, likes the radio and prefers talk to music. Who, at the Internet’s inception, would have foreseen the rise and rise of radio, or the renaissance of that archaic word, “wireless”? I hear, above the launderette din of stomach and bowels, the news, wellspring of all bad dreams. Driven by a self-harming compulsion, I listen closely to analysis and dissent. Repeats on the hour, regular half-hourly summaries don’t bore me. I even tolerate the BBC World Service and its puerile blasts of synthetic trumpets and xylophone to separate the items. In the middle of a long, quiet night I might give my mother a sharp kick. She’ll wake, become insomniac, reach for the radio. Cruel sport, I know, but we are both better informed by the morning.

And she likes podcast lectures, and self-improving audio books—Know Your Wine in fifteen parts, biographies of seventeenth-century playwrights, and various world classics. James Joyce’s Ulysses sends her to sleep, even as it thrills me. When, in the early days, she inserted her earbuds, I heard clearly, so efficiently did sound waves travel through jawbone and clavicle, down through her skeletal structure, swiftly through the nourishing amniotic. Even television conveys most of its meagre utility by sound. Also, when my mother and Claude meet, they occasionally discuss the state of the world, usually in terms of lament, even as they scheme to make it worse. Lodged where I am, nothing to do but grow my body and mind, I take in everything, even the trivia—of which there is much.

For Claude is a man who prefers to repeat himself. A man of riffs. On shaking hands with a stranger—I’ve heard this twice—he’ll say, “Claude, as in Debussy.” How wrong he is. This is Claude as in property developer who composes nothing, invents nothing. He enjoys a thought, speaks it aloud, then later has it again, and—why not?—says it again. Vibrating the air a second time with this thought is integral to his pleasure. He knows you know he’s repeating himself. What he can’t know is that you don’t enjoy it the way he does. This, I’ve learned from a Reith lecture, is what is known as a problem of reference.

Here’s an example both of Claude’s discourse and of how I gather information. He and my mother have arranged by telephone (I hear both sides) to meet in the evening. Discounting me, as they tend to—a candlelit dinner for two. How do I know about the lighting? Because when the hour comes and they are shown to their seats I hear my mother complain. The candles are lit at every table but ours.

There follows in sequence Claude’s irritated gasp, an imperious snapping of dry fingers, the kind of obsequious murmur that emanates, so I would guess, from a waiter bent at the waist, the rasp of a lighter. It’s theirs, a candlelit dinner. All they lack is the food. But they have the weighty menus on their laps—I feel the bottom edge of Trudy’s across the small of my back. Now I must listen again to Claude’s set piece on menu terms, as if he’s the first ever to spot these unimportant absurdities. He lingers on “pan-fried.” What is pan but a deceitful benediction on the vulgar and unhealthy fried? Where else might one fry his scallops with chilli and lime juice? In an egg timer? Before moving on, he repeats some of this with a variation of emphasis. Then, his second favourite, an American import, “steel-cut.” I’m silently mouthing his exposition even before he’s begun when a slight tilt in my vertical orientation tells me that my mother is leaning forwards to place a restraining finger on his wrist and say, sweetly, divertingly, “Choose the wine, darling. Something splendid.”

I like to share a glass with my mother. You may never have experienced, or you will have forgotten, a good burgundy (her favourite) or a good Sancerre (also her favourite) decanted through a healthy placenta. Even before the wine arrives—tonight, a Jean-Max Roger Sancerre—at the sound of a drawn cork, I feel it on my face like the caress of a summer breeze. I know that alcohol will lower my intelligence. It lowers everybody’s intelligence. But oh, a joyous, blushful Pinot Noir, or a gooseberried Sauvignon, sets me turning and tumbling across my secret sea, reeling off the walls of my castle, the bouncy castle that is my home. Or so it did when I had more space. Now I take my pleasures sedately, and by the second glass my speculations bloom with that licence whose name is poetry. My thoughts unspool in well-sprung pentameters, end-stopped and run-on lines in pleasing variation. But she never takes a third, and it wounds me.

“I have to think of baby,” I hear her say as she covers her glass with a priggish hand. That’s when I have it in mind to reach for my oily cord, as one might a velvet rope in a well-staffed country house, and pull sharply for service. What ho! Another round here for us friends!

But no, she restrains herself for love of me. And I love her—how could I not? The mother I have yet to meet, whom I know only from the inside. Not enough! I long for her external self. Surfaces are everything. I know her hair is “straw fair,” that it tumbles in “coins of wild curls” to her “shoulders the white of apple flesh,” because my father has read aloud to her his poem about it in my presence. Claude too has referred to her hair, in less inventive terms. When she’s in the mood, she’ll make tight braids to wind around her head, in the style, my father says, of Yulia Tymoshenko. I also know that my mother’s eyes are green, that her nose is a “pearly button,” that she wishes she had more of one, that separately both men adore it as it is and have tried to reassure her. She’s been told many times that she’s beautiful, but she remains sceptical, which confers on her an innocent power over men, so my father told her one afternoon in the library. She replied that if this was true, it was a power she’d never looked for and didn’t want. This was an unusual conversation for them and I listened intently. My father, whose name is John, said that if he had such a power over her or women in general, he couldn’t imagine giving it up. I guessed, from the sympathetic wave motion which briefly lifted my ear from the wall, that my mother had emphatically shrugged, as if to say, So men are different. Who cares? Besides, she told him out loud, whatever power she was supposed to have was only what men conferred in their fantasies. Then the phone rang, my father walked away to take the call, and this rare and interesting conversation about those that have power was never resumed.

But back to my mother, my untrue Trudy, whose apple-flesh arms and breasts and green regard I long for, whose inexplicable need for Claude pre-dates my first awareness, my primal is, and who often speaks to him, and he to her, in pillow whispers, restaurant whispers, kitchen whispers, as if both suspect that wombs have ears.

I used to think that their discretion was no more than ordinary, amorous intimacy. But now I’m certain. They airily bypass their vocal cords because they’re planning a dreadful event. Should it go wrong, I’ve heard them say, their lives will be ruined. They believe that if they’re to proceed, they should act quickly, and soon. They tell each other to be calm and patient, remind each other of the cost of their plan’s miscarriage, that there are several stages, that each must interlock, that if any single one fails, then all must fail “like old-fashioned Christmas tree lights”—this impenetrable simile from Claude, who rarely says anything obscure. What they intend sickens and frightens them, and they can never speak of it directly. Instead, wrapped in whispers are ellipses, euphemisms, mumbled aporia followed by throat-clearing and a brisk change of subject.

One hot, restless night last week, when I thought both were long asleep, my mother said suddenly into the darkness, two hours before dawn by the clock downstairs in my father’s study, “We can’t do it.”

And straight away Claude said flatly, “We can.” And then, after a moment’s reflection, “We can.”

TWO

Now, to my father, John Cairncross, a big man, my genome’s other half, whose helical twists of fate concern me greatly. It’s in me alone that my parents forever mingle, sweetly, sourly, along separate sugar-phosphate backbones, the recipe for my essential self. I also blend John and Trudy in my daydreams—like every child of estranged parents, I long to remarry them, this base pair, and so unite my circumstances to my genome.

My father comes by the house from time to time and I’m overjoyed. Sometimes he brings her smoothies from his favourite place on Judd Street. He has a weakness for these glutinous confections that are supposed to extend his life. I don’t know why he visits us, for he always leaves in mists of sadness. Various of my conjectures have proved wrong in the past, but I’ve listened carefully and for now I’m assuming the following: that he knows nothing of Claude, remains moonishly in love with my mother, hopes to be back with her one day soon, still believes in the story she has given him that the separation is to give them each “time and space to grow” and renew their bonds. That he is a poet without recognition and yet he persists. That he owns and runs an impoverished publishing house and has seen into print the first collections of successful poets, household names, and even one Nobel laureate. When their reputations swell, they move away like grown children to larger houses. That he accepts the disloyalty of poets as a fact of life and, like a saint, delights in the plaudits that vindicate the Cairncross Press. That he’s saddened rather than embittered by his own failure in verse. He once read aloud to Trudy and me a dismissive review of his poetry. It said that his work was outdated, stiffly formal, too “beautiful.” But he lives by poetry, still recites it to my mother, teaches it, reviews it, conspires in the advancement of younger poets, sits on prize committees, promotes poetry in schools, writes essays on poetry for small magazines, has talked about it on the radio. Trudy and I heard him once in the small hours. He has less money than Trudy and far less than Claude. He knows by heart a thousand poems.

Amsterdam

Amsterdam In Between the Sheets

In Between the Sheets Atonement

Atonement My Purple Scented Novel

My Purple Scented Novel The Innocent

The Innocent The Children Act

The Children Act Enduring Love

Enduring Love Sweet Tooth

Sweet Tooth On Chesil Beach

On Chesil Beach The Child in Time

The Child in Time The Comfort of Strangers

The Comfort of Strangers Black Dogs

Black Dogs The Daydreamer

The Daydreamer Nutshell

Nutshell The Cement Garden

The Cement Garden Saturday

Saturday Machines Like Me

Machines Like Me The Cockroach

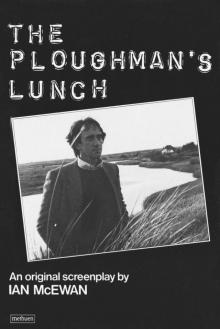

The Cockroach The Ploughman’s Lunch

The Ploughman’s Lunch