- Home

- Ian Mcewan

The Cement Garden Page 2

The Cement Garden Read online

Page 2

I remembered my father waiting and I hurried downstairs. My mother, Julie and Sue were standing about talking in the kitchen as I passed through. They did not seem to notice me. My father was lying face down on the ground, his head resting on the newly spread concrete. The smoothing plank was in his hand. I approached slowly, knowing I had to run for help. For several seconds I could not move away. I stared wonderingly, just as I had a few minutes before. A light breeze stirred a loose corner of his shirt.

Subsequently there was a great deal of activity and noise. An ambulance came, and my mother went off in it with my father who was laid out on a stretcher and covered with a red blanket. In the living room Sue cried and Julie comforted her. The radio was playing in the kitchen. I went back outside after the ambulance had left to look at our path. I did not have a thought in my head as I picked up the plank and carefully smoothed away his impression in the soft, fresh concrete.

CHAPTER TWO

DURING THE following year Julie trained for the school athletics team. She already held the local under-eighteen records for the 100 and 220-yard sprint. She could run faster than anyone I knew. Father never took her seriously, he said it was daft in a girl, running fast, and not long before he died he refused to come to a sports meeting with us. We attacked him bitterly; even Mother joined in. He laughed at our exasperation. Perhaps he really intended to be there, but we left him alone and sulked among ourselves. On the day, because we did not ask him to come, he forgot and never saw, in the last month of his life, his oldest daughter star of all the field. He missed the pale brown slim legs flickering across the green like blades, or me, Tom, Mother and Sue running across the enclosure to cover Julie with kisses when she took her third race. In the evenings she often stayed at home to wash her hair and iron the pleats in her navy blue school skirt. She was one of a handful of daring girls at school who wore starched white petticoats beneath their skirts to fill them out and make them swirl when they turned on their heel. She wore stockings and black knickers, strictly forbidden. She had a clean white blouse five days a week. Some mornings she gathered her hair in the nape of her neck with a brilliant white ribbon. All this took considerable preparation each evening. I used to sit around, watching her at the ironing board, getting on her nerves.

She had boyfriends at school, but she never really let them get near her. There was an unspoken family rule that none of us ever brought friends home. Her closest friends were girls, the most rebellious, the ones with reputations. I sometimes saw her at school at the far end of a corridor surrounded by a small noisy group. But Julie herself gave little away; she dominated her group and heightened her reputation with a disruptive, intimidating quietness. I had some status at school as Julie’s brother but she never spoke to me there or acknowledged my presence.

At some point during the same period my spots were so thoroughly established across my face that I abandoned all the rituals of personal hygiene. I no longer washed my face or hair or cut my nails or took baths. I gave up brushing my teeth. In her quiet way my mother reproved me continuously, but I now felt proudly beyond her control. If people really liked me, I argued, they would take me as I was. In the early morning my mother came into my bedroom and exchanged my dirty clothes for clean ones. On weekends I lay in bed till the afternoon and then took long solitary walks. In the evenings I watched Julie, listened to the radio or just sat. I had no close friends at school.

I frequently stared at myself in mirrors, sometimes for as long as an hour. One morning, shortly before my fifteenth birthday, I was searching in the gloom of our huge hallway for my shoes when I glimpsed myself in a full-length mirror which leaned against the wall. My father had always intended to secure it. Colored light through the stained glass above the front door illuminated from behind stray fibers of my hair. The yellowish semidarkness obscured the humps and pits of my complexion. I felt noble and unique. I stared at my own image till it began to dissociate itself and paralyze me with its look. It receded and returned to me with each beat of my pulse, and a dark halo throbbed above its head and shoulders. “Tough,” it said to me. “Tough.” And then louder, “shit … piss … arse.” From the kitchen my mother called my name in weary admonition.

From a bowl of fruit I picked out an apple and went to the kitchen. I slouched in the doorway and watched the family at breakfast and tossed the apple in my hand, catching it with crisp smacks against the palm. Julie and Sue read schoolbooks while they were eating. My mother, drained by another night without sleep, was not eating. Her sunken eyes were gray and watery. With whines of irritation Tom was trying to push his chair nearer hers. He wanted to sit in her lap, but she complained he was too heavy. She arranged the chair for him and ran her fingers through her hair.

The issue was whether Julie would walk to school with me. We used to go together every morning, but now she preferred not to be seen with me. I continued to toss the apple, imagining it made them all uneasy. My mother watched me steadily.

“Come on Julie,” I said at last. Julie refilled her teacup.

“I’ve got things to do,” she said firmly. “You go on.”

“What about you then, Sue?”

My younger sister did not look up from her book. She murmured, “Not going yet.”

My mother reminded me gently that I had not had my breakfast but I was already on my way through the hall. I slammed the front door hard and crossed the road. Our house had once stood in a street full of houses. Now it stood on empty land where stinging nettles grew round torn corrugated tin. The other houses were knocked down for a motorway they never built. Sometimes kids from the tower blocks came to play near our house, but usually they went farther up the road to the empty prefabs to kick the walls down and pick up what they could find. Once they set fire to one, and no one cared very much. Our house was old and large. It was built to look a little like a castle, with thick walls, squat windows and crenellations above the front door. Seen from across the road it looked like the face of someone concentrating, trying to remember.

No one ever came to visit us. Neither my mother nor my father when he was alive had any real friends outside the family. They were both only children, and all my grandparents were dead. My mother had distant relatives in Ireland whom she had not seen since she was a child. Tom had a couple of friends he sometimes played with in the street, but we never let him bring them in the house. There was not even a milkman in our road now. As far as I could remember, the last people to visit the house had been the ambulance men who took my father away.

I stood there several minutes wondering whether to return indoors and say something conciliatory to my mother. I was about to move on when the front door opened and Julie slipped out. She wore her black gabardine school raincoat belted tightly about her waist and the collar was turned up. She turned quickly to catch the front door before it slammed and the coat, skirt and petticoat spun with her, the desired effect. She had not seen me yet. I watched her sling her satchel over her shoulder. Julie could run like the wind, but she walked as though asleep, dead slow, straight-backed and in a very straight line. She often appeared deep in thought, but when we asked her she always protested that her mind was empty.

She did not see me until she was across the road and then she half smiled, half pouted and remained silent. Her silence made us all a little afraid of her, but again she would protest, her voice musical with bemusement, that she was the one who was afraid. It was true, she was shy—there was a rumor she never spoke in class without blushing—but she had the quiet strength and detachment and lived in the separate world of those who are, and secretly know they are, exceptionally beautiful. I walked alongside her and she stared ahead, her back straight as a ruler, her lips softly pursed.

A hundred yards on, our road ran into another street. A few terraced houses remained. The rest, and all the houses in the next street across, had been cleared to make way for four twenty-story tower blocks. They stood on wide aprons of cracked asphalt where weeds were pushing through.

They looked even older and sadder than our house. All down their concrete sides were colossal stains, almost black, caused by the rain. They never dried out. When Julie and I reached the end of our road I lunged at her wrist and said, “Carry your satchel, miss.” Julie pulled her arm away and went on walking. I danced backward in her path. Her brooding silences turned me into a nuisance.

“Wanna fight? Wanna race?” Julie lowered her eyes and kept to her course. I said in a normal voice, “What’s wrong?”

“Nothing.”

“Are you pissed off?”

“Yes.”

“With me?”

“Yes.”

I paused before speaking again. Already Julie was drifting away, absorbed in some internal vision of her anger. I said, “Because of Mum?” We were drawing level with the first of the tower blocks and we could see through into the lobby. A gang of kids from another school were gathered around the lift shaft. They lolled against the walls without talking. They were waiting for someone to come down in the lift. I said, “I’ll go back then.” I stopped. Julie shrugged and made a sudden movement with her hand that made it clear she was leaving me behind.

Back on our street I met Sue. She walked with a book held open in front of her. Her satchel was strapped tight and high across her shoulders. Tom walked a few yards behind. From the look on his face it was clear there had been another scene getting him out of the house. I felt easier with Sue. She was two years younger than I, and if she had secrets I was not intimidated by them. Once I saw in her bedroom a lotion she had bought to “dissolve” her freckles. Her face was long and delicate, the lips colorless and the eyes small and tired-looking with pale, almost invisible lashes. With her high forehead and wispy hair she sometimes really did look like a girl from another planet. We did not stop, but as we passed Sue looked up from her book and said, “You’re going to be late.”

And I muttered, “Forgot something.” Tom was preoccupied with his own dread of school and did not notice me. The realization that Sue was taking him to school to save Mother the walk increased my guilt, and I walked faster.

I walked round the side of the house to the back garden and watched my mother through one of the kitchen windows. She sat at the table with the mess of our breakfast and four empty chairs in front of her. Immediately facing her was my untouched bowl of porridge. One hand was in her lap, the other on the table, the arm crooked as if ready to receive her head. Near her was a squat black bottle which contained her pills. Her face mixed Julie’s features with Sue’s, as though she were their child. The skin was smooth and taut over the fine cheekbones. Each morning she painted on her lips a perfect bow in deepest red. But her eyes, set in dark skin wrinkled like a peach stone, were sunk so far into her skull she seemed to stare out from a deep well. She stroked the thick dark curls at the back of her head. On some mornings I would find a nest of her hair floating in the toilet. I always flushed it away first. Now she stood up and with her back to me began to clear the table.

When I was eight years old I came home from school one morning pretending to be seriously ill. My mother indulged me. She put me into my pajamas, carried me to the sofa in the living room and wrapped me in a blanket. She knew I had come home to monopolize her while my father and two sisters were out of the house. Perhaps she was glad to have someone at home with her during the day. Till the late afternoon I lay there and watched as she went about her work, and when she was in another part of the house I listened closely. I was struck by the obvious fact of her independent existence. She went on, even when I was away at school. These were the things she did. Everybody went on. At that time the insight had been memorable but not painful. Now, as I watched her stoop to knock eggshells from the table into the rubbish pail, the same, simple recognition conveyed both sadness and menace, in unbearable combination. She was not a particular invention of mine, or of my sisters, though I continued to invent and ignore her. As she was moving an empty milk bottle, she turned suddenly toward the window. I stepped back quickly. As I ran down the side path I heard her open the back door and call my name. I caught a glimpse of her as she stepped round the corner of the house. She called after me again as I set off down the street. I ran all the way, imagining her voice above the row of my feet on the pavement.

“Jack … Jack.”

I caught up with my sister Sue just as she was turning through the school gates.

CHAPTER THREE

I KNEW IT was morning, and I knew it was a bad dream. By an effort of will I could wake myself. I tried to move my legs, to make one foot touch the other. Any slight sensation would be enough to establish me in the world outside my dream. I was being followed by someone I could not see. In their hands they carried a box, and they wanted me to look inside, but I hurried on. I paused for a moment and attempted to move my legs again or open my eyes. But someone was coming with the box, there was no time and I had to run on. Then we came face to face. The box, wooden and hinged, might once have contained expensive cigars. The lid was lifted half an inch or so, too dark to see inside. I ran on in order to gain time, and this time I succeeded in opening my eyes. Before they closed, I saw my bedroom, my school shirt lying across a chair, a shoe upside down on the floor. Here was the box again. I knew there was a small creature inside, kept captive against its will and stinking horribly. I tried to call out, hoping to wake myself with the sound of my own voice. No sound left my throat, and I could not even move my lips. The lid of the box was being lifted again. I could not turn and run for I had been running all night and now I had no choice but to look inside. With great relief I heard the door of my bedroom open and footsteps across the floor. Someone was sitting on the edge of my bed, right by my side, and I could open my eyes.

My mother sat in such a way as to trap my arms inside the bedclothes. It was half past eight by my alarm and I was going to be late for school. My mother would have been up for two hours already. She smelled of the bright pink soap she used. She said, “It’s time we had a talk, you and I.” She crossed one leg over the other and rested her hands on her knees. Her back, like Julie’s, was very straight. However ill she was, she always sat very straight. I felt at a disadvantage lying on my back, and I struggled to sit up. But she said, “You lie there a moment.”

“I’m going to be late,” I said.

“You lie there a moment,” she repeated with a heavy emphasis on the last word. “I want to talk to you.”

My heart beating very fast, I stared past her head at the ceiling. I was barely out of my dream.

“Look at me,” she said. “I want to look at your eyes.”

I looked into her eyes and they roved anxiously across my face. I saw my own swollen reflection.

“Have you looked at your eyes in a mirror lately?” she said.

“No,” I said untruthfully.

“Your pupils are very large, did you know that?” I shook my head. “And there are bags under your eyes even though you’ve just woken up.” She paused. Downstairs I could hear the others eating breakfast. “And do you know why that is?” Again I shook my head, and again she paused. She leaned forward and spoke urgently. “You know what I’m talking about don’t you?” My heart thudded in my ears.

“No,” I said.

“Yes you do, my boy. You know what I’m talking about, I can see you do.”

I had no choice but to confirm this with my silence. This sternness did not suit her at all; there was a flat, playacting tone in her voice, the only way she could deliver her difficult message.

“Don’t think I don’t know what’s going on. You’re growing into a young man now, and I’m very proud you are … these are things your father would have been telling you ….” We looked away; we both knew this was not true. “Growing up is difficult, but if you carry on the way you are, you’re going to do yourself a lot of damage, damage to your growing body.

“Damage …” I echoed.

“Yes, look at yourself,” she said in a softer voice. “You can’t get up in the morn

ings, you’re tired all day, you’re moody, you don’t wash yourself or change your clothes, you’re rude to your sisters and to me. And we both know why that is. Every time….” She trailed away and, rather than look at me, stared down at her hands in her lap. “Every time… you do that, it takes two pints of blood to replace it.” She looked at me defiantly.

“Blood,” I whispered. She leaned forward and kissed me lightly on the cheek.

“You don’t mind me saying this to you, do you?”

“No, no,” I said. She stood up.

“One day, when you’re twenty-one, you’ll turn round and thank me for telling you what I’ve been telling you.” I nodded. She stooped over me and affectionately ruffled my hair and then quickly left the room.

My sisters and I no longer played together on Julie’s bed. The games ceased not long after Father died, although it was not his death that brought them to an end. Sue became reluctant. Perhaps she had learned something at school and was ashamed of herself for letting us do things to her. I was never certain because it was not something we could talk about. And Julie was more remote now. She wore makeup and had all kinds of secrets. In the dinner queue at school I once overheard her refer to me as her “kid brother,” and I was stung. She had long conversations with Mother in the kitchen that would break off if Tom, Sue or I came in suddenly. Like my mother, Julie made remarks to me about my hair or my clothes, not gently though, but with scorn.

Amsterdam

Amsterdam In Between the Sheets

In Between the Sheets Atonement

Atonement My Purple Scented Novel

My Purple Scented Novel The Innocent

The Innocent The Children Act

The Children Act Enduring Love

Enduring Love Sweet Tooth

Sweet Tooth On Chesil Beach

On Chesil Beach The Child in Time

The Child in Time The Comfort of Strangers

The Comfort of Strangers Black Dogs

Black Dogs The Daydreamer

The Daydreamer Nutshell

Nutshell The Cement Garden

The Cement Garden Saturday

Saturday Machines Like Me

Machines Like Me The Cockroach

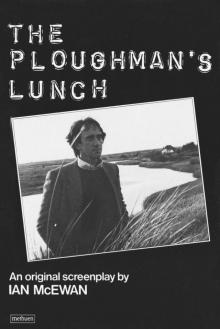

The Cockroach The Ploughman’s Lunch

The Ploughman’s Lunch