- Home

- Ian Mcewan

Machines Like Me Page 2

Machines Like Me Read online

Page 2

With the inheritance, I could have bought a place somewhere north of the river, Notting Hill, or Chelsea. She might even have joined me. She would’ve had space for all the books that were boxed up in her father’s garage in Salisbury. I saw a future without Adam, the future that was mine until yesterday: an urban garden, high ceilings with plaster mouldings, stainless-steel kitchen, old friends to dinner. Books everywhere. What to do? I could take him, or it, back, or sell it online and take a small loss. I gave it a hostile look. The hands were palms down on the table, the hawkish face remained angled towards the hands. My foolish infatuation with technology! Another fondue set. Best to get away from the table before I impoverished myself with a single swipe of my father’s old claw hammer.

I drank no more than half a glass, then I returned to the bedroom to distract myself with the Asian currency markets. All the while I listened out for footsteps in the flat above me. Late into the evening, I watched TV to catch up on the Task Force that would soon set off across 8,000 miles of ocean to recapture what we then called the Falkland Islands.

*

At thirty-two, I was completely broke. Wasting my mother’s inheritance on a gimmick was only one part of my problem – but typical of it. Whenever money came my way, I caused it to disappear, made a magic bonfire of it, stuffed it into a top hat and pulled out a turkey. Often, though not in this recent case, my intention was to conjure a far larger sum with minimal effort. I was a mug for schemes, semi-legal ruses, cunning shortcuts. I was for grand and brilliant gestures. Others made them and flourished. They borrowed money, put it to interesting use, and remained enriched even as they settled their debts. Or they had jobs, professions, as I once had, and enriched themselves more modestly, at a steady rate. I meanwhile leveraged or, rather, shorted myself into genteel ruin, into two damp ground-floor rooms in the dull, no-man’s-land of Edwardian terraced streets between Stockwell and Clapham, south London.

I grew up in a village near Stratford, Warwickshire, the only child of a musician father and community-nurse mother. Compared to Miranda’s, my childhood was culturally undernourished. There was no time or space for books, or even music. I took a precocious interest in electronics but ended up with an anthropology degree from an unregarded college in the south Midlands; I did a conversion course to law and, once qualified, specialised in tax. A week after my twenty-ninth birthday I was struck off, and came close to a short spell in prison. My hundred hours of community service convinced me that I should never have a regular job again. I made some money out of a book I wrote at high speed on artificial intelligence: lost to a life-extension-pill scheme. I made a reasonable sum on a property deal: lost to a car-rental scheme. I was left some funds by a favourite uncle who had prospered by way of a heat-pump patent: lost to a medical-insurance scheme.

At thirty-two, I was surviving by playing the stock and currency markets online. A scheme, just like the rest. For seven hours a day I bowed before my keyboard, buying, selling, hesitating, punching the air one moment, cursing the next, at least, at the beginning. I read market reports, but I believed I was dealing in a random system and mostly relied on guesses. Sometimes I leaped ahead, sometimes I plunged, but on average through the year I made about as much as the postman. I paid my rent, which was low in those days, ate and dressed well enough, and thought I was beginning to stabilise, learning to know myself. I was determined that my thirties would be a superior performance to my twenties.

But my parents’ pleasant family home was sold just as the first convincing artificial person came on the market. 1982. Robots, androids, replicates were my passion, even more so after my research for the book. Prices were bound to fall, but I had to have one straight away, an Eve by preference, but an Adam would do.

It could have turned out differently. My previous girlfriend, Claire, was a sensible person who trained to be a dental nurse. She worked in a Harley Street practice and she would have talked me out of Adam. She was a woman of the world, of this one. She knew how to arrange a life. And not only her own. But I offended her with an act of undeniable disloyalty. She disowned me in a scene of regal fury, at the end of which she threw my clothes out into the street. Lime Grove. She never spoke to me again and belonged at the top of my list of errors and failures. She could have saved me from myself.

But. In the interests of balance, let that unsaved self speak up. I didn’t buy Adam to make money. On the contrary. My motives were pure. I handed over a fortune in the name of curiosity, that steadfast engine of science, of intellectual life, of life itself. This was no passing fad. There was a history, an account, a time-deposit, and I had a right to draw on it. Electronics and anthropology – distant cousins whom late modernity has drawn together and bound in marriage. The child of that coupling was Adam.

So, I appear before you, witness for the defence, after school, 5 p.m., typical specimen for my time – short trousers, scabby knees, freckles, short back and sides, eleven years old. I’m first in line, waiting for the lab to open and for ‘Wiring Club’ to begin. Presiding is Mr Cox, a gentle giant with carroty hair who teaches physics. My project is to build a radio. It’s an act of faith, an extended prayer that has taken many weeks. I have a base of hardboard, six inches by nine, easily drilled. Colours are everything. Blue, red, yellow and white wires run their modest courses around the board, turning at right angles, disappearing below to emerge elsewhere and be interrupted by bright nodules, tiny vividly striped cylinders – capacitors, resistors – then an induction coil I have wound myself, then an op-amp. I understand nothing. I follow a wiring diagram as a novice might murmur scripture. Mr Cox gives softly spoken advice. I clumsily solder one piece, one wire or component to another. The smoke and smell of solder is a drug I inhale deeply. I include in my circuit a toggle switch made of Bakelite which, I’ve persuaded myself, came out of a fighter plane, a Spitfire surely. The final connection, three months after my beginning, is from this piece of dark brown plastic to a nine-volt battery.

It’s a cold, windy dusk in March. Other boys are hunched over their projects. We are twelve miles away from Shakespeare’s hometown, in what will come to be known as a ‘bog-standard’ comprehensive school. An excellent place, in fact. The fluorescent ceiling lights come on. Mr Cox is on the far side of the lab with his back turned. I don’t want to attract his attention in case of failure. I throw the switch and – miracle – hear the sound of static. I jiggle the variable-tuning capacitor: music, terrible music, as I think, because violins are involved. Then comes the rapid voice of a woman, not speaking English.

No one looks up, no one is interested. Building a radio is nothing special. But I’m speechless, close to tears. No technology since will amaze me as much. Electricity, passing through pieces of metal carefully arranged by me, snatch from the air the voice of a foreign lady sitting somewhere far away. Her voice sounds kindly. She isn’t aware of me. I’ll never learn her name or understand her language, and never meet her, not knowingly. My radio, with its irregular blobs of solder on a board, appears no less a wonder than consciousness itself arising from matter.

Brains and electronics were closely related, so I discovered through my teens as I built simple computers and programmed them myself. Then complicated computers. Electricity and bits of metal could add up numbers, make words, pictures, songs, remember things and even turn speech into writing.

When I was seventeen, Peter Cox persuaded me to study physics at a local college. Within a month I was bored and looking to change. The subject was too abstract, the maths was beyond me. And by then I’d read a book or two and was taking an interest in imaginary people. Heller’s Catch-18, Fitzgerald’s The High-Bouncing Lover, Orwell’s The Last Man in Europe, Tolstoy’s All’s Well that Ends Well – I didn’t get much further and yet I saw the point of art. It was a form of investigation. But I didn’t want to study literature – too intimidating, too intuitive. A single-sheet course summary I picked up in the college library announced anthropology as ‘the science of people in their

societies through space and time’. Systematic study, with the human factor thrown in. I signed up.

The first thing to learn: my course was pitifully underfunded. No bunking off for a year to the Trobriand Islands where, I read, it was taboo to eat in front of others. It was good manners to eat alone, with your back turned to friends and family. The islanders had spells to make ugly people beautiful. Children were actively encouraged to be sexual with each other. Yams were the viable currency. Women determined the status of men. How strange and bracing. My view of human nature had been shaped by the mostly white population crammed into the southern quarter of England. Now I was set free into bottomless relativism.

At the age of nineteen I wrote a wise essay on honour cultures entitled ‘Mind-forged Manacles?’ Dispassionately, I gathered up my case studies. What did I know or care? There were places where rape was so common it didn’t have a name. A young father’s throat was cut for failing in his duties to an ancient feud. Here was a family eager to kill a daughter for being seen holding hands with a lad from the wrong religious group. There, elderly women keenly assisted in the genital mutilation of their granddaughters. What of the instinctive parental impulses to love and protect? The cultural signal was louder. What of universal values? Upended. Nothing like this in Stratford-upon-Avon. It was all about the mind, the tradition, the religion – nothing but software, I now thought, and best regarded in value-free terms.

Anthropologists did not pass judgement. They observed and reported on human variety. They celebrated difference. What was wicked in Warwickshire was unremarkable in Papua New Guinea. Locally, who was to say what was good or bad? Certainly not a colonial power. I derived from my studies some unfortunate conclusions about ethics which led me a few years later to the dock in a county court, accused of conspiring with others to mislead the tax authorities on a grand scale. I did not attempt to persuade His Honour that far from his court might be a coconut beach where such conspiracy was respected. Instead, I came to my senses just before I addressed the judge. Morals were real, they were true, good and bad inhered in the nature of things. Our actions must be judged on their terms. This was what I’d assumed before anthropology came along. In quavering, hesitant tones I apologised abjectly to the court and dodged a custodial sentence.

*

When I entered the kitchen in the morning, later than usual, Adam’s eyes were open. They were pale blue, flecked with minuscule vertical rods of black. The eyelashes were long and thick, like a child’s. But his blink mechanism had not yet kicked in. It was set at irregular intervals and adjusted for mood and gestures, and primed to react to the actions and speech of others. Reluctantly, I’d read the handbook into the night. He was equipped with a blink reflex to protect his eyes from flying objects. At present, his gaze was empty of meaning or intent and therefore unaffecting, as lifeless as the stare of a shop-window mannequin. So far, he was showing none of the fractional movements that warmly typify the human head. Elsewhere, no body language at all. When I felt for the pulse in his wrist, I found nothing – a heartbeat without a pulse. His arm was heavy to lift, resistant at the elbow joint, as though rigor mortis was about to set in.

I turned my back on him and made coffee. Miranda was on my mind. Everything had changed. Nothing had changed. During my near sleepless night, I’d remembered that she was visiting her father. She would have gone straight to Salisbury from her seminar. I saw her on her train from Waterloo, sitting with an unread book on her lap, staring at the rushing landscape, the dip and rise of telephone lines, not thinking of me. Or thinking only of me. Or recalling a boy at her seminar who’d tried to out-stare her.

I watched the TV news on my phone. A brilliant mosaic in sound and sparkling seaside light. Portsmouth. The Task Force ready to depart. Most of the country was in a dream-theatre, in historical dress. Late medieval. Seventeenth century. Early nineteenth. Ruffs, hose, hooped skirts, powdered wigs, eyepatches, wooden legs. Accuracy was unpatriotic. Historically, we were special and the fleet was bound for success. TV and press encouraged a vague collective memory of enemies defeated – the Spanish, the Dutch, the Germans twice this century, the French from Agincourt to Waterloo. A fly-past by fighter jets. A young man in combat gear, fresh out of Sandhurst, narrowed his eyes as he told an interviewer of the difficulties ahead. A superior officer spoke of his men’s unshakeable resolve. I was moved, even as I disliked it. When a massed band of Highland pipers marched towards their ship’s gangplank, my spirits swelled. Then back to the studio for charts, arrows, logistics, objectives, sane voices in agreement. For diplomatic moves. For the prime minister in her trim blue suit on the steps of Downing Street.

I warmed to it, even though I often declared myself against it all. I loved my country. What a venture, what wild courage. Eight thousand miles. What decent people putting their lives at risk. I took a second coffee next door, made the bed to give the room the appearance of a workplace, and sat down to reflect a while on the state of the world’s markets. The prospect of war had sent the FTSE down a further one per cent. Still in patriotic mood, I assumed an Argie defeat and took a position on a toy and novelty group that made Union Jacks on sticks for people to wave. I also invested in two champagne importers, and bet on a big recovery generally. Merchant-navy ships had been requisitioned to transport troops to the South Atlantic. A friend who worked in asset management in the City told me that his company was predicting that some would be sunk. It made sense to short the major players in the insurance markets and invest in South Korean shipbuilders. I was in no mood for such cynicism.

My desktop computer, bought second-hand from a Brixton junk shop, dated from the mid-sixties and was slow. It took me an hour to arrange the position on the flag maker. I would have been quicker if I’d had my thoughts under control. When I wasn’t thinking about Miranda and listening out for her footsteps in the flat above me, I was thinking about Adam and whether I should sell him off, or start making decisions about his personality. I sold sterling and thought more about Adam. I bought gold and thought again about Miranda. I sat on the lavatory and wondered about Swiss francs. Over a third coffee I asked myself what else a victorious nation might spend its money on. Beef. Pubs. TV sets. I took positions on all three and felt virtuous, a part of the war effort. Soon it was time for lunch.

I sat facing Adam again while I ate a cheese and pickle sandwich. Any further signs of life? Not at first glance. His gaze, directed over my left shoulder, was still dead. No movement. But five minutes later I glanced up by chance and was actually looking at him when he began to breathe. I heard first a series of rapid clicks, then a mosquito-like whine as his lips parted. For half a minute nothing happened, then his chin trembled and he made an authentic gulping sound as he snatched his first mouthful of air. He didn’t need oxygen, of course. That metabolic necessity was years away. His first exhalation was so long in coming that I stopped eating and tensely waited. It came at last – silently, through his nostrils. Soon his breathing assumed a steady rhythm, his chest expanded and contracted appropriately. I was spooked. With his lifeless eyes, Adam had the appearance of a breathing corpse.

How much of life we ascribe to the eyes. If only his were closed, I thought, he’d at least have the appearance of a man in a trance. I left my sandwich and went to stand by him and, out of curiosity, put my hand close to his mouth. His breath was moist and warm. Clever. In the user’s manual I’d read that he urinated once a day in the late morning. Also clever. As I went to close his right eye, my forefinger brushed against his eyebrow. He flinched and violently jerked his head away from me. Startled, I moved back. Then I waited. For twenty seconds or more nothing happened, then, with a smooth, soundless movement, infinitesimally slow, the tilt of his shoulders, the angle of his head moved towards their former positions. His rate of breathing was undisturbed. Mine and my pulse had accelerated. I was standing several feet away, fascinated by the way he settled back, like a balloon gently deflating. I decided against closing his eyes. While I was waiting fo

r something more from him, I heard Miranda moving around in the flat upstairs. Back from Salisbury. Wandering in and out of her bedroom. Once again I felt the troubled thrill of undeclared love, and that was when I had the first stirrings of an idea.

*

That afternoon I should have been making and losing money at my computer. Instead, I watched from the great height of a helicopter as the leading ships of the Task Force rounded Portland Bill and filed by Chesil Beach. The very place names deserved a respectful salute. How brilliant. Onwards! I kept thinking. And then, Go back! Soon, the fleet came along the Jurassic coast, where herds of dinosaurs once grazed on giant ferns. Suddenly, we were down among the people of Lyme Regis gathering on the Cobb. Some had binoculars, many had the very flags I had in mind, plastic on a wooden stick. A news team might have handed them around. Vox pops. Gentle local voices of hard-working women, tight with emotion. Tough old coves who’d fought in Crete and Normandy, nodding to themselves, giving nothing away. Oh, how I wished I too believed. But I could! A long lens mounted somewhere on the Lizard showed the tiny receding blobs of ships heading bravely out onto the big swell of the open sea to the sound of husky Rod Stewart, while I tried not to be tearful.

What turmoil on a weekday afternoon. A new kind of being at my dining table, the woman I newly loved six feet above my head, and the country at old-fashioned war. But I was tolerably disciplined and had promised myself seven hours every day. I turned off the TV and went to my screen. Waiting for me was the email from Miranda that I’d hoped for.

I knew I would never get rich. The sums I moved around, safely spread across scores of opportunities, were small. Over the month I had done well out of solid-state batteries but had lost almost as much to rare earth element futures – a foolish leap into the known. But I was keeping myself out of a career, an office job. This was my least bad option in the pursuit of freedom. I worked on through the afternoon, resisting the temptation to look in on Adam, even though I guessed he would be fully charged by now. Next step was downloading his updates. Then, those problematic personal preferences.

Amsterdam

Amsterdam In Between the Sheets

In Between the Sheets Atonement

Atonement My Purple Scented Novel

My Purple Scented Novel The Innocent

The Innocent The Children Act

The Children Act Enduring Love

Enduring Love Sweet Tooth

Sweet Tooth On Chesil Beach

On Chesil Beach The Child in Time

The Child in Time The Comfort of Strangers

The Comfort of Strangers Black Dogs

Black Dogs The Daydreamer

The Daydreamer Nutshell

Nutshell The Cement Garden

The Cement Garden Saturday

Saturday Machines Like Me

Machines Like Me The Cockroach

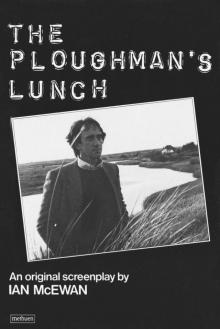

The Cockroach The Ploughman’s Lunch

The Ploughman’s Lunch