- Home

- Ian Mcewan

The Cockroach Page 2

The Cockroach Read online

Page 2

He cleared his throat and managed to say, ‘Let’s get on, shall we.’ He was stuck for any further remark, but luckily a fellow, older than the rest and wearing a suit as expensive-looking as his own, pushed through and, seizing Jim by the elbow, propelled him along the corridor.

‘A quick word.’

A door swung open and they went through. ‘Your coffee’s in here.’

They were in the Cabinet room. Halfway down the long table by the largest chair was a tray of coffee, which the prime minister approached with such avidity that over the last few steps he broke into a run. He hoped to arrive ahead of his companion and snatch a moment with the sugar bowl. But by the time he was lowering himself into the chair, with minimal decorum, his coffee was being poured. There was no sugar on the tray. Not even milk. But in the grey shadow cast by his saucer, visible only to him, was a dying bluebottle. Every few seconds its wings trembled. With some effort, Jim wrenched his gaze away while he listened. He was beginning to think he might sneeze.

‘About the 1922 Committee. The usual bloody suspects.’

‘Ah, yes.’

‘Last night.’

‘Of course.’

When the bluebottle’s wings shook they made the softest rustle of acquiescence.

‘I’m glad you weren’t there.’

When a bluebottle has been dead for more than ten minutes it tastes impossibly bitter. Barely alive or just deceased, it has a cheese flavour. Stilton, mostly.

‘Yes?’

‘It’s a mutiny. And all over the morning papers.’

There was nothing to be done. The prime minister had to sneeze. He had felt it building. Probably the lack of dust. He gripped the chair. For an explosive instant he thought he had passed out.

‘Bless you. There was talk of a no-confidence vote.’

When he opened his unhelpfully lidded eyes, the fly had gone. Blown away. ‘Fuck.’

‘That’s what I thought.’

‘Where is it? I mean, where’s the sense in—’

‘The usual. You’re a closet Clockwiser. Not with the Project. Not a true go-it-alone man. Getting nothing through parliament. Zero backbone. That sort of thing.’

Jim drew his cup and saucer towards him. No. He lifted the stainless steel pot. Not under there either.

‘I’m as Reversalist as any of them.’

By his silence his special adviser, if that was what he was, appeared to disagree. Then he said, ‘We need a plan. And quick.’

It was only now that the Welsh accent was evident. Wales? A small country far to the west, hilly, rain-sodden, treacherous. Jim was finding that he knew things, different things. He knew differently. His understanding, like his vision, was narrowed. He lacked the broad and instant union with the entirety of his kind, the boundless resource of the oceanic pheromonal. But he had finally remembered in full his designated mission.

‘What do you suggest?’

There came a loud single rap, the door opened and a tall man with a generous jaw, bottle-black swept-back hair and pinstripe suit strode in.

‘Jim, Simon. Mind if I join you? Bad news. Encryption just in from—’

Simon interrupted. ‘Benedict, this is private. Kindly bugger off.’

Without a shift in expression, the foreign secretary turned and left the room, closing the door behind him with exaggerated care.

‘What I resent,’ Simon said, ‘about these privately educated types is their sense of entitlement. Excluding you, of course.’

‘Quite. What’s the plan?’

‘You’ve said it yourself. Take a step towards the hardliners, they scream for more. Give them what they want, they piss on you. Things go wrong with the Project, they blame anyone and everyone. Especially you.’

‘So?’

‘There’s a wobble in the public mood. The focus groups are telling a new story. Our pollster phoned in the results last night. There’s general weariness. Creeping fear of the unknown. Anxiety about what they voted for, what they’ve unleashed.’

‘I heard about those results,’ the prime minister lied. It was important to maintain face.

‘Here’s the point. We should isolate the hardliners. Confidence motion my arse! Prorogue parliament for a few months. Astound the bastards. Or even better, change tack. Swing—’

‘Really?’

‘I mean it. You’ve got to swing—’

‘Clockwise?’

‘Yes! Parliament will fall at your feet. You’ll have a majority – just.’

‘But the will of the p—’

‘Fuck the lot of them. Gullible wankers. It’s a parliamentary democracy and you’re in charge. The house is stalled. The country’s tearing itself apart. We had that ultra-Reversalist beheading a Clockwise MP in a supermarket. A Clockwise yob pouring milkshake over a high-profile Reversalist.’

‘That was shocking,’ the prime minister agreed. ‘His blazer had only just been cleaned.’

‘The whole thing’s a mess. Jim, time to call it off.’ Then he added softly, ‘It’s in your power.’

The PM stared into his adviser’s face, taking it in for the first time. It was narrow and long, hollow at the temples, with little brown eyes and a tight rosebud mouth. He had a grey three-day beard and wore trainers and a black silk suit over a Superman T-shirt.

‘What you’re saying is very interesting,’ the PM said at last.

‘It’s my job to keep you in office and this is the only way.’

‘It’d be a…a…’ Jim struggled for the word. He knew several variants in pheromone, but they were fading. Then he had it. ‘A U-turn!’

‘Not quite. I’ve been back through some of your speeches. Enough there to get you off the hook. Difficulties. Doubts. Delays. Sort of stuff the hardliners hate you for. Shirley can prepare the ground.’

‘Very interesting indeed.’ Jim stood up and stretched. ‘I need to talk to Shirley myself before Cabinet. And I’ll need a few minutes alone.’

He began to walk round the long table towards the door. He was coming to feel some pleasure in his stride and a new sense of control. Improbable as it had seemed, it was possible to feel stable on only two feet. It hardly bothered him to be so far off the ground. And he was glad now not to have eaten a bluebottle in another man’s presence. It might not have gone down well.

Simon said, ‘I’ll wait for your thoughts, then.’

Jim reached the door and let the fingers of one strange hand rest lightly on the handle. Yes, he could drive this soft new machine. He turned, taking pleasure in doing it slowly, until he was facing the adviser, who had not moved from his chair.

‘You can have them now. I want your resignation letter on my desk within the half hour and I want you out of the building by eleven.’

* * *

*

The press secretary, Shirley, a tiny, affable woman dressed entirely in black and wearing outsized black-rimmed glasses, bore an uncomfortable resemblance to a hostile stag beetle. But she and the PM got on well as she fanned out before him a slew of unfriendly headlines. ‘Bin Dim Jim!’ ‘In the name of God, go!’ Following Simon’s usage and calling the hard-line Reversalists on the backbenches ‘the usual bloody suspects’ helped give the news a harmless and comic aspect. Together, Jim and Shirley chuckled. But the more serious papers agreed that a no-confidence vote might well succeed. The prime minister had alienated both the Clockwise and Reversalist tendencies within his party. He was too much the appeaser. By reaching out to both wings, he had alienated nearly everyone. ‘In politics,’ one well-known columnist wrote, ‘bipartisan is a death rattle.’ Even if the motion failed, ran the general view, the very fact of a vote undermined his authority.

‘We’ll see about that,’ Jim said, and Shirley laughed loudly, as if he had just told a brilliant joke.

He was on his way out to s

it by himself and prepare for the next meeting. He gave instructions to Shirley for Simon’s resignation letter to be released to the media just before he stepped out into the street to deny to reporters that anything was amiss. Shirley expressed no surprise at her colleague’s sacking. Instead, she nodded cheerfully as she gathered up the morning’s papers.

It was bad form for all but the PM to be late for a Cabinet meeting. By the time he entered the room, everyone was in place round the table. He took his seat between the chancellor and the foreign secretary. Was he nervous? Not exactly. He was tensed and ready, like a sprinter on the blocks. His immediate concern was to appear plausible. Just as his fingers had known how to knot a tie, so the PM knew that his opening words were best preceded by silence and steady eye contact around the room.

It was in those few seconds, as he met the bland gaze of Trevor Gott, the chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, then the home secretary, attorney general, leader of the house, trade, transport, minister without portfolio, that in a startling moment of instant recognition, an unaccustomed, blossoming, transcendent joy swept through him, through his heart and down his spine. Outwardly he remained calm. But he saw it clearly. Nearly all of his Cabinet shared his convictions. Far more important than that, and he had not known this until now, they shared his origins. When he had made his way up Whitehall on that perilous night, he thought he was on a lonely mission. It had never occurred to him that the mighty burden of his task was shared, that others like him were heading towards separate ministries to inhabit other bodies and take up the fight. A couple of dozen, a little swarm of the nation’s best, come to inhabit and embolden a faltering leadership.

There was, however, a minor problem, an irritant, an absence. The traitor at his side. He had seen it at a glance. In paradise there was always a devil. Just one. It was likely that among their number there was a brave messenger who had not made it from the palace, who had been sacrificed underfoot, just as he himself almost had, on the pavement outside the gates. When Jim had looked into the eyes of Benedict St John, the foreign secretary, he had come against the blank unyielding wall of a human retina and could go no further. Impenetrable. Nothing there. Merely human. A fake. A collaborator. An enemy of the people. Just the sort who might rebel and vote to bring down his own government. This would have to be dealt with. The opportunity would present itself. Not now.

But here were the rest, and he recognised them instantly through their transparent, superficial human form. A band of brothers and sisters. The metamorphosed radical Cabinet. As they sat round the table, they gave no indication of who they really were, and what they all knew. How eerily they resembled humans! Looking into and beyond the various shades of grey, green, blue and brown of their mammalian eyes, right through to the shimmering blattodean core of their being, he understood and loved his colleagues and their values. They were precisely his own. Bound by iron courage and the will to succeed. Inspired by an idea as pure and thrilling as blood and soil. Impelled towards a goal that lifted beyond mere reason to embrace a mystical sense of nation, of an understanding as simple and as simply good and true as religious faith.

What also bound this brave group was the certainty of deprivation and tears to come, though, to their regret, they would not be their own. But certainty, too, that after victory there would come to the general population the blessing of profound and ennobling self-respect. This room, in this moment, was no place for the weak. The country was about to be set free from a loathsome servitude. From the best, the shackles were already dropping. Soon, the Clockwise incubus would be pitchforked from the nation’s back. There are always those who hesitate by an open cage door. Let them cower in elective captivity, slaves to a corrupt and discredited order, their only comfort their graphs and pie-charts, their arid rationality, their pitiful timidity. If only they knew, the momentous event had already slipped from their control, it had moved beyond analysis and debate and into history. It was already unfolding, here at this table. The collective fate was being forged in the heat of the Cabinet’s quiet passion. Hard Reversalism was mainstream. Too late to go back!

TWO

The origins of Reversalism are obscure and much in dispute, among those who care. For most of its history, it was considered a thought experiment, an after-dinner game, a joke. It was the preserve of eccentrics, of lonely men who wrote compulsively to the newspapers in green ink. Of the sort who might trap you in a pub and bore you for an hour. But the idea, once embraced, presented itself to some as beautiful and simple. Let the money flow be reversed and the entire economic system, even the nation itself, will be purified, purged of absurdities, waste and injustice. At the end of a working week, an employee hands over money to the company for all the hours that she has toiled. But when she goes to the shops, she is generously compensated at retail rates for every item she carries away. She is forbidden by law to hoard cash. The money she deposits in her bank at the end of a hard day in the shopping mall attracts high negative interest rates. Before her savings are whittled away to nothing, she is therefore wise to go out and find, or train for, a more expensive job. The better, and therefore more costly, the job she finds for herself, the harder she must shop to pay for it. The economy is stimulated, there are more skilled workers, everyone gains. The landlord must tirelessly purchase manufactured goods to pay for his tenants. The government acquires nuclear power stations and expands its space programme in order to send out tax gifts to workers. Hotel managers bring in the best champagne, the softest sheets, rare orchids and the best trumpet player in the best orchestra in town, so that the hotel can afford its guests. The next day, after a successful gig at the dance floor, the trumpeter will have to shop intensely in order to pay for his next appearance. Full employment is the result.

Two significant seventeenth-century economists, Joseph Mun and Josiah Child, made passing references to the reverse circulation of money, but dismissed the idea without giving it much attention. At least, we know the theory was in circulation. There is nothing in Adam Smith’s seminal The Wealth of Nations, nor in Malthus or Marx. In the late nineteenth century, the American economist Francis Amasa Walker expressed some interest in redirecting the flow of money, but he did so, apparently, in conversation rather than in his considerable writings. At the crucial Bretton Woods conference in 1944, which framed the post-war economic order and founded the International Monetary Fund, there occurred in one of the sub-committees a fully minuted, impassioned plea for Reversalism by the Paraguayan representative Jesus X. Velasquez. He gained no supporters, but he is generally credited with being the first to use the term in public.

The idea was occasionally attractive in Western Europe to groups on the right or far right, because it appeared to limit the power and reach of the state. In Britain, for example, while the top rate of tax was still eighty-three per cent, the government would have had to hand out billions to the most dedicated shoppers. Keith Joseph was rumoured to have made an attempt to interest Margaret Thatcher in ‘reverse-flow economics’ but she had no time for it. And in a BBC interview in April 1980, Sir Keith insisted that the rumour was entirely false. Through the nineties, and into the noughties, Reversalism kept a modest profile among various private discussion groups and lesser-known right-of-centre think tanks.

When the Reversalist Party arrived spectacularly on the scene with its populist, anti-elitist message, there were many, even among its opponents, who were already familiar with the ‘counter-flow’ thesis. After the Reversalists won the approval of the American president, Archie Tupper, and even more so when it began to lure voters away, the Conservative Party began, in reaction, a slow drift to the right and beyond. But to the Conservative mainstream, Reversalism remained, in the ex-chancellor George Osborne’s words, ‘the world’s daftest idea’. No one knows which economist or journalist came up with the term ‘Clockwisers’ for those who preferred money to go round in the old and tested manner. Many claimed to have been first.

On the l

eft, especially the ‘old left’, there was always a handful who were soft on Reversalism. One reason was that they believed it would empower the unemployed. With no jobs to pay for and plenty of time for shopping, the jobless could become seriously rich, if not in hoarded money, then in goods. Meanwhile, the established rich would be able to do nothing with their wealth other than spend it on gainful employment. When working-class Labour voters grasped how much they could earn by getting a son into Eton or a daughter into Cheltenham Ladies’ College, they too began to raise their aspirations and defect to the cause.

In order to shore up its electoral support and placate the Reversalist wing of the party, the Conservatives promised in their 2015 election manifesto a referendum on reversing the money flow. The result was the unexpected one, largely due to an unacknowledged alliance between the working poor and the old of all classes. The former had no stake in the status quo and nothing to lose, and they looked forward to bringing home essential goods as well as luxuries, and to being cash rich, however briefly. The old, by way of cognitive dimming, were nostalgically drawn to what they understood to be a proposal to turn back the clock. Both groups, poor and old, were animated to varying degrees by nationalist zeal. In a brilliant coup, the Reversalist press managed to present their cause as a patriotic duty and a promise of national revival and purification: everything that was wrong with the country, including inequalities of wealth and opportunity, the north–south divide and stagnating wages, was caused by the direction of financial flow. If you loved your country and its people, you should upend the existing order. The old flow had merely served the interests of a contemptuous ruling elite. ‘Turn the Money Around’ became one of many irresistible slogans.

Amsterdam

Amsterdam In Between the Sheets

In Between the Sheets Atonement

Atonement My Purple Scented Novel

My Purple Scented Novel The Innocent

The Innocent The Children Act

The Children Act Enduring Love

Enduring Love Sweet Tooth

Sweet Tooth On Chesil Beach

On Chesil Beach The Child in Time

The Child in Time The Comfort of Strangers

The Comfort of Strangers Black Dogs

Black Dogs The Daydreamer

The Daydreamer Nutshell

Nutshell The Cement Garden

The Cement Garden Saturday

Saturday Machines Like Me

Machines Like Me The Cockroach

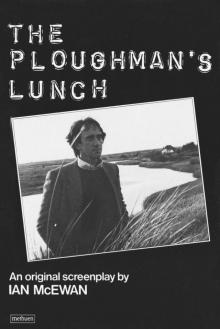

The Cockroach The Ploughman’s Lunch

The Ploughman’s Lunch